Several of my clients have recently made comments which seem to lead back to the same big questions: What do I know about them, and how do I understand what’s happening in counselling?

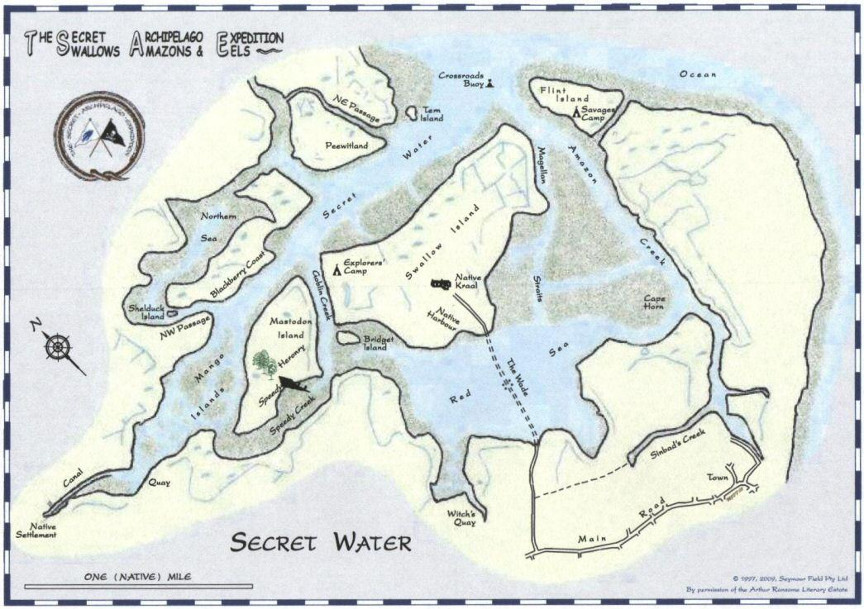

As a child, I lived and breathed Arthur Ransome’s “Swallows and Amazons” books. I loved the idea of setting out with a pile of sketched maps, a pencil and a bottle of ink, to explore uncharted waters.

As a therapist, I also start with a “blank map”, a vague and hazy idea of what might be happening for the child or young person. The first shapes are formed from my consultation with the child’s parents, who tell me something about the child’s background and experiences, their unique personality, and the problems they are experiencing. My training and experience give me some clues as to where to look for more details. Lush vegetation suggests a source of fresh water nearby; two adjacent towns are likely to be linked by a transport route.

One of the purposes of therapy is to help my client to understand their world – their external environment and networks, and their own behaviour and responses – well enough to feel safe and to make effective choices. My role in the exploration is decided by the child or young person, always the captain of their own ship.

Sometimes I am the ship’s mate, looking after supplies, providing safety and sustenance for the journey, but rarely involved in the exploration itself.

Often I am the scribe, the mapmaker for the expedition. While my client explores new areas, tries out theories and tests the potential of the terrain, it is my job to make sense of the things they are finding, to connect the parts together and, sometimes, to translate the new discoveries for parents, friends or teachers.

Occasionally, I am allowed to run ahead, learning about the child for myself and coming back with a tentative report of my findings. “I’m not sure, but I think there might be a clearing over there – I wonder whether it would be good for us to explore it?” Some children and young people like to compare their map with mine often, to be explicit about the work that we’re doing and its meaning for them. Others keep their maps carefully folded in their pockets, and we only occasionally compare our notes, maybe when we are feeling very lost or approaching a review with parents or carers.

Some maps take shape easily: I feel as if I have a fairly clear understanding of the child’s problems and their use of therapy. At other times, I have to work a lot harder to understand how different bits of a child’s play fit together, and what makes them important. I always need to be open to the possibility of revising my ideas in the light of new information. What appeared to be an island is in fact a promontory, joined to the mainland by a fragile track; an irritating bramble turns out to be providing vital protection, or perhaps occasional fruit.

The important thing for me to remember is that while a clear and complete map might make my job easier, it isn’t the aim of therapy. The most important outcome is for my client to be able to look around their island (or their river, lake, swamp or countryside) and say:

“I know this land well enough; I can live here. I can feel safe and comfortable, I can predict and manage its challenges, I can make use of its opportunities. This is my world and I can live in it.”

2 comments for “Mapping Therapy”